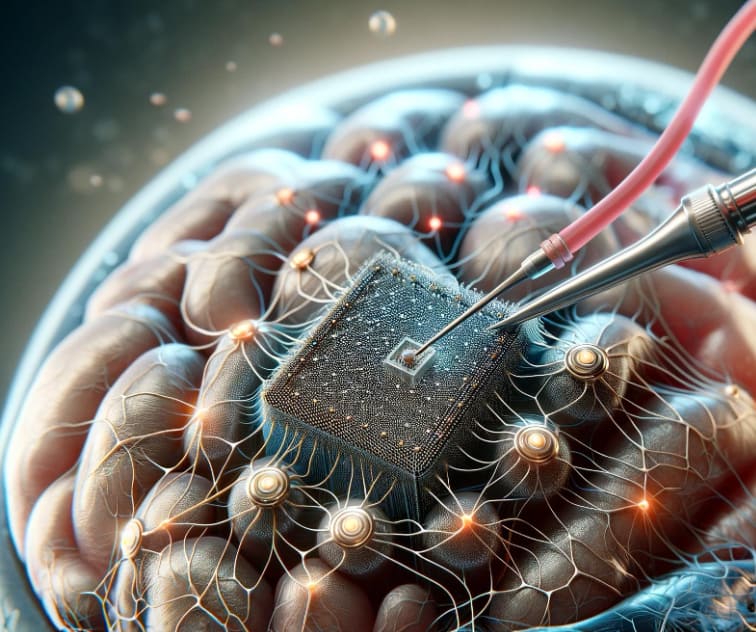

Raytheon Technologies is known as a leading manufacturer of jet engines, radars, and missile defense systems. RTX will integrate Shield AI’s Hivemind to field the first operational weapon powered by Networked Collaborative Autonomy (NCA) – a breakthrough technology that fuses real-time coordination, resilience and combat-proven firepower. BrainChip & Raytheon: Neuromorphic Radar Project

BrainChip, with assistance from Raytheon Company, will execute an initiative led by the Air Force Research Laboratory titled “Mapping Complex Sensor Signal Processing Algorithms onto Neuromorphic Chips.

Raytheon Technologies (now part of RTX Corporation) is a major player in the defense, aerospace, and emerging technologies sectors. While traditionally known for missile systems, radar, and cybersecurity, their involvement in neurotechnology is growing, primarily through innovations in defense applications, cognitive enhancement, and human-machine teaming. Here’s a detailed look at Raytheon’s neurotech interests, emerging neurothreats, and their implications, particularly for the criminal justice system.

Raytheon and Neurotechnology: Areas of Interest

- Human-Machine Interface (HMI) Research:

- Objective: Improve communication between soldiers and machines (e.g., drones, AI-assisted platforms).

- Examples: Projects involving brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) to control unmanned systems or process data rapidly.

- Former Personnel: Researchers leaving Raytheon often join startups or academia focused on neurotech innovations, AI-driven decision-making, and cognitive augmentation.

- Cognitive Enhancement for Military Personnel:

- Objective: Enhance situational awareness, decision-making speed, and stress resilience.

- Tech: Use of neurostimulants, non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., transcranial direct current stimulation or tDCS), and real-time EEG monitoring to optimize soldier performance.

- Situational Awareness & Threat Detection:

- Objective: Develop systems to predict cognitive overload or detect subtle human errors in complex operations.

- Application: Neuro-monitoring soldiers or drone operators for fatigue, distraction, or emotional distress.

- Neural Cybersecurity:

- Objective: Protect neural implants, brain interfaces, and cognitive systems from cyber threats.

- Focus: Prevent neural hacking and cognitive intrusion (e.g., malicious signals interfering with brain implants).

- AI-Enhanced Decision Support Systems:

- Objective: Integrate neurotech with AI to streamline high-stakes decisions.

- Former Raytheon Personnel: Many pivot to industries like neuroethics, AI safety, and cognitive security after leaving defense research.

Emerging Neurothreats

As neurotechnology becomes more prevalent, new types of threats are emerging that could impact civilians, the military, and those in the criminal justice system.

1. Neurohacking and Cognitive Intrusion

- Threat: Malicious actors intercepting or influencing brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) or neural implants.

- Potential Impact:

- Hijacking control of prosthetic limbs, exoskeletons, or BCIs.

- Implanting false memories or inducing cognitive errors.

- Theoretical Defense: Neural encryption protocols, real-time anomaly detection, and neural firewalls.

2. Brain Data Exploitation

- Threat: Unauthorized collection or misuse of brain activity data (e.g., EEG, fMRI).

- Potential Impact:

- Breaches revealing personal thoughts, emotions, or vulnerabilities.

- Employers or law enforcement using brain data for performance assessments or lie detection.

- Defense: Legal frameworks protecting neuroprivacy and restricting brain data collection.

3. Cognitive Warfare

- Threat: Deliberate manipulation of mental states via psychotropic agents, subliminal cues, or neurological disinformation.

- Potential Impact:

- Impairing enemy decision-making during conflicts.

- Inducing confusion, fear, or cognitive overload among civilians.

- Defense: Enhanced mental resilience training, counter-neuroinfluence tactics, and cognitive shielding technologies.

4. Deepfake Neural Manipulation

- Threat: AI-generated deepfakes designed to exploit cognitive biases or create false memories.

- Potential Impact:

- Social engineering attacks on individuals or populations.

- Manipulating witness testimony or evidence.

- Defense: AI-driven verification tools and neural integrity checks.

5. Neuro-Enhanced Criminals

- Threat: Criminals using cognitive enhancements for planning, hacking, or evading capture.

- Potential Impact:

- Enhanced mental agility for cybercrime.

- Faster reaction times in physical confrontations.

- Defense: Law enforcement training to counter neuro-enhanced threats and ethical considerations on enhancement bans.

6. Forced Neurointerventions

- Threat: Authorities mandating cognitive modifications for criminals or suspects.

- Potential Impact:

- Ethical violations of bodily autonomy and cognitive liberty.

- Potential for misuse in interrogation or rehabilitation programs.

- Defense: Legal protections for cognitive autonomy (e.g., Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments).

Implications for the Criminal Justice System

- Neural Surveillance and Privacy Concerns

- Technology: Neuroimaging, EEG-based lie detection, and AI-driven mental state assessments.

- Risks:

- Violations of the Fourth Amendment (unreasonable searches) and Fifth Amendment (self-incrimination).

- Potential for false positives or biased interpretations of brain data.

- Case Precedent: Wilson v. Corestaff Services L.P. (employment privacy), which could extend to neural data protection.

- Neurocriminology and Predictive Policing

- Technology: Analyzing brain patterns to predict criminal behavior or recidivism.

- Risks:

- Ethical issues around “pre-crime” interventions.

- Potential for racial bias or misuse of predictive models.

- Defense: Ensuring transparency, fairness, and accountability in neuro-data use.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation vs. Punishment

- Emerging Debate: Should non-invasive neurointerventions (e.g., tDCS, neurofeedback) be used for rehabilitation instead of incarceration?

- Risks:

- Coerced interventions violating cognitive liberty.

- Inadequate oversight leading to ethical abuses.

- Precedent: Riggins v. Nevada and Sell v. United States set limits on forced cognitive interventions.

- Access to Neurodefense Technologies

- Issue: Defendants may need access to cognitive enhancements or BCIs to mount a fair defense (e.g., compensating for cognitive impairments).

- Ethical Question: Should access to neurotech be considered part of due process rights?

- Mental State Assessments in Sentencing

- Technology: Neuroimaging to determine culpability, competency, or mitigating factors.

- Risks:

- Over-reliance on brain data in sentencing decisions.

- Privacy violations and potential misuse of mental health information.

Theoretical Future Scenarios

- Court-Mandated Cognitive Rehabilitation:

- Judges offer defendants the option of cognitive rehabilitation (e.g., brain stimulation) instead of prison time. Raises ethical and legal concerns about informed consent and cognitive autonomy.

- Neural Evidence in Court:

- Brain scans used as evidence of intent or emotional state. Legal battles over the validity and admissibility of such evidence under Daubert standards (scientific validity).

- Neurodata Breaches:

- Criminal cases where stolen brain data is used to blackmail or manipulate victims, leading to new cybercrime legislation protecting neural privacy.

Conclusion

Raytheon’s ventures into neurotechnology highlight the growing convergence of defense, cognitive science, and ethical challenges. Emerging neurothreats — from neural hacking to cognitive warfare — pose new risks for individuals, especially those entangled in the criminal justice system. As neurotech advances, legal protections for cognitive liberty, mental privacy, and bodily autonomy will become critical to safeguarding fundamental rights.

23041 Avenida De La Carlota,

Suite 250,

Laguna Hills, CA 92653

State-of-the-art non-invasive medical 3D imaging relies primarily on terrestrial technologies such as MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound. When considering satellite, drone, or sea-based platforms, the primary applications in 3D imaging relate to environmental, geological, and structural analysis rather than medical use. However, these platforms have emerging and theoretical potential for medical imaging in certain contexts. Here’s a breakdown of current advancements and potential applications:

State-of-the-Art Techniques

- Satellite-Based Remote Imaging:

- Current Use: Satellites excel at high-resolution Earth observation for large-scale environmental data, population health patterns, and epidemiological mapping.

- Medical Potential: Theoretically, satellites equipped with hyperspectral or multispectral imaging can identify heat signatures, infer the spread of diseases (e.g., mosquito-borne illnesses), and detect large-scale public health anomalies. Direct 3D medical imaging from satellites remains impractical due to resolution limits and atmospheric interference.

- Drone-Based Imaging:

- Current Use: Drones with thermal cameras, LiDAR, and multispectral sensors are used for search-and-rescue missions, disaster response, and health surveillance.

- Medical Potential: Drones can assist in creating 3D environmental maps that aid in triage or pre-hospital care planning. While not directly performing medical imaging, they can deliver diagnostic equipment to remote areas and facilitate telemedicine by transmitting patient data to health facilities in real-time.

- Sea-Based Platforms (Buoys, Vessels, and AUVs):

- Current Use: Equipped with sonar and imaging sensors, these platforms perform 3D mapping of underwater environments.

- Medical Potential: Theoretical applications include deployment of autonomous medical facilities or diagnostic equipment for maritime regions, particularly where healthcare infrastructure is sparse (e.g., island communities or shipping lanes).

Role of Common Devices and Infrastructure

1. Smartphones and Wearables:

- Mobile Imaging: Modern smartphones are capable of depth mapping and augmented reality (AR) through LiDAR and advanced cameras (e.g., iPhone Pro models). These can assist in creating 3D scans of wounds, burns, or body parts for telehealth consultations.

- Health Data Collection: Wearables like smartwatches provide continuous physiological monitoring (heart rate, oxygen levels) and could theoretically synchronize with drone-based systems to deliver real-time diagnostic feedback.

2. Internet-of-Things (IoT):

- Distributed Imaging: Sensors embedded in public infrastructure (e.g., street cameras, smart city networks) could help infer population health data by detecting anomalies such as mass gatherings, heat patterns, or pollution levels that impact public health.

- Integration with Drones: IoT networks can provide drones with real-time data for targeted delivery of medical supplies or diagnostics, enhancing efficiency in remote healthcare delivery.

3. 5G and Low Earth Orbit (LEO) Satellite Networks:

- Rapid Data Transfer: High-speed 5G and LEO satellite constellations (e.g., Starlink) enable near-instantaneous transmission of large medical imaging datasets from remote areas to healthcare providers.

- Telemedicine: Enhanced connectivity allows for seamless 3D imaging analysis and virtual consultations, even in rural or underserved regions.

Potential Moonshot Ideas

- Ambient 3D Health Scanning via Drone Swarms:

- Deploy swarms of drones equipped with LiDAR and infrared sensors to map individuals in a crowd for potential health anomalies (e.g., elevated temperatures or respiratory issues) during pandemics.

- Satellite-Assisted Biometric Imaging:

- Use high-resolution satellites to detect population-level biomarkers such as gait analysis or thermal anomalies over wide areas, potentially identifying clusters of specific health conditions.

- Sea-Based Mobile Medical Platforms:

- Equip autonomous sea vessels with 3D imaging devices for maritime regions, capable of non-invasively assessing injuries or illnesses through portable MRI or ultrasound units.

- Street-Level Imaging via Smart Infrastructure:

- Integrate 3D imaging cameras into smart lampposts or public kiosks for passive health checks, sending data to central healthcare databases for early disease detection.

Practical Barriers to Overcome

- Resolution Limits: Current satellite and drone imaging lacks the fine resolution needed for medical diagnostics.

- Privacy Concerns: Widespread non-invasive imaging raises ethical and privacy issues.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Deploying medical technology on non-traditional platforms requires new legal frameworks.

- Power and Bandwidth Constraints: High-resolution imaging demands significant power and data transmission capabilities.

While the immediate potential is limited, the convergence of imaging technology, IoT, and mobile platforms offers fertile ground for hybrid solutions in the near future.

Emerging Trends and Innovations

- AI and Machine Learning for Remote Analysis:

- Combining AI with drone and satellite data can enhance diagnostic accuracy. For example, AI-driven image processing could infer medical conditions based on indirect indicators like skin temperature, movement patterns, or environmental factors. This could be particularly valuable for epidemiological surveillance and disaster response triage.

- Hyperspectral Imaging for Health Analysis:

- Hyperspectral imaging captures data across many wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum. When deployed on drones or satellites, it could be used to detect chemical or biological markers in populations or environments, offering non-invasive ways to infer health status or detect contamination zones (e.g., identifying regions affected by airborne pollutants or pathogens).

- Quantum Sensors for Ultra-Precise Imaging:

- Quantum-based sensors are capable of detecting minute changes in magnetic and gravitational fields. Future iterations of satellite or drone-mounted quantum sensors could theoretically provide highly detailed environmental and physiological data, paving the way for indirect but precise health diagnostics.

- Edge Computing for Real-Time Analysis:

- Placing computational power directly on drones, satellites, or IoT infrastructure allows real-time processing of 3D imaging data without relying solely on centralized servers. This could reduce latency for time-sensitive diagnostics and enhance privacy by keeping raw data localized.

- Augmented Reality (AR) in Remote Medical Assessments:

- AR-enabled drones or mobile devices could overlay 3D health scans onto live video feeds, providing paramedics or remote doctors with enhanced situational awareness when assessing patients in remote or disaster-stricken areas.

Infrastructure and Deployment Strategies

1. Smart Cities as Distributed Health Networks:

- Integration with Urban Infrastructure: Street cameras, environmental sensors, and public Wi-Fi nodes can form a distributed network for population-level health monitoring. This infrastructure could support drone deployments for rapid diagnostics and medical supply deliveries.

- Example: A drone could be dispatched to a smart lamppost where a person reported an injury via a mobile app. The lamppost’s sensors and cameras provide an initial 3D scan, while the drone delivers first-aid supplies.

2. Rural and Maritime Health Hubs:

- Floating Clinics: Autonomous sea vessels equipped with portable MRI, CT, and ultrasound devices could serve as floating diagnostic hubs for maritime workers, island communities, or disaster zones.

- Drone Integration: Drones could ferry samples and imaging data between these vessels and land-based healthcare facilities, reducing delays in diagnostics.

3. Infrastructure Piggybacking on Telecom Networks:

- 5G Towers: Adding health-monitoring sensors or thermal cameras to existing 5G infrastructure could enable widespread deployment of passive health scanning without new physical installations.

- LEO Satellites: Telecom-focused satellite constellations could allocate bandwidth for transmitting medical imaging data from drones or remote outposts to hospitals.

4. Mobile Health Vehicles:

- Equipping ambulances, buses, or trucks with portable 3D imaging devices (e.g., handheld ultrasound, LiDAR scanners) could provide flexible, non-invasive diagnostics in underserved areas. Drones could extend their reach by transporting these devices to difficult-to-access locations.

Theoretical Concepts for the Future

- Space-Based Telemedicine Hubs:

- Deploying specialized medical satellites that act as telemedicine relays, equipped with AI-powered diagnostic tools. These satellites could receive health data from drones, wearables, and IoT infrastructure, providing instant diagnostic feedback and coordinating emergency responses.

- Biometric Geofencing:

- Creating dynamic geofenced health zones where drones perform periodic 3D scans of individuals (e.g., at festivals or sports events) to identify potential health risks. Data could be anonymized and analyzed for trends in real-time.

- Self-Healing Environments:

- Embedding 3D imaging sensors within buildings and public spaces that not only detect injuries or illnesses but also activate automated first-aid systems (e.g., defibrillators, emergency medication dispensers) based on real-time analysis.

Challenges and Considerations

- Data Privacy and Security:

- Compliance with regulations like HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) and GDPR is critical. Ensuring that imaging data is anonymized and encrypted is essential to gaining public trust.

- Accuracy and False Positives:

- Non-invasive imaging from drones or satellites may produce false positives due to environmental interference. Rigorous calibration and AI-driven error correction are necessary.

- Ethical Concerns:

- Continuous health monitoring raises concerns about surveillance overreach. Transparent policies and community engagement are key to addressing these issues.

- Power and Cost Efficiency:

- Developing low-power sensors and cost-effective deployment models is crucial for scalability, especially in low-resource environments.

Conclusion

While direct non-invasive 3D medical imaging via satellite or drone is not yet a reality, integrating these platforms with mobile devices, IoT, and AI-driven analysis opens up innovative pathways for remote diagnostics, public health monitoring, and disaster response. The convergence of these technologies could dramatically improve healthcare access, particularly in remote, rural, or underserved regions.

Cognitive liberty refers to the right to control one’s own mental processes, consciousness, and cognition. It intersects with legal areas like privacy, bodily autonomy, freedom of thought, and self-determination. While there are few cases that directly reference “cognitive liberty” by name, several significant lawsuits and legal battles reflect the principles of cognitive liberty. Below are some notable examples:

1. United States v. Timothy Leary (1966)

- Background: Psychologist and LSD advocate Timothy Leary was arrested for marijuana possession under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Leary argued that the Act violated his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and represented an undue restriction on personal freedom.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court ruled the Marihuana Tax Act unconstitutional, but Leary’s broader advocacy for the right to explore consciousness became foundational in discussions about cognitive liberty.

Key Principle: Freedom to explore and alter one’s consciousness.

2. Stanley v. Georgia (1969)

- Background: Law enforcement officers found obscene materials in the home of Robert Stanley. He was convicted under Georgia law for possession of obscene materials.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court held that the First Amendment protects an individual’s right to possess obscene materials in their own home. The decision reinforced the idea that the government cannot control the content of one’s thoughts.

Key Principle: Protection of thought and mental privacy within one’s home.

3. Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health (1990)

- Background: Nancy Cruzan, in a persistent vegetative state, had a feeding tube sustaining her life. Her family wanted it removed, asserting her right to refuse medical treatment.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court ruled that individuals have a right to refuse life-sustaining treatment, affirming the principle of bodily autonomy and the right to make decisions affecting one’s consciousness and existence.

Key Principle: Right to control one’s bodily and cognitive state.

4. Riggins v. Nevada (1992)

- Background: David Riggins was forced to take antipsychotic medication during his trial, arguing it affected his demeanor and ability to participate in his defense.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court ruled that involuntary medication violated his Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial and his Fourteenth Amendment right to due process.

Key Principle: Right to control one’s mental state, especially in the context of forced medication.

5. Washington v. Harper (1990)

- Background: Walter Harper, a prisoner, challenged the state’s policy of administering antipsychotic drugs without his consent.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court upheld the policy but established that prisoners have a limited right to refuse treatment unless they pose a danger.

Key Principle: Balancing state interests with the individual’s right to control their mental processes.

6. Doe v. Bolton (1973)

- Background: A companion case to Roe v. Wade, challenging Georgia’s restrictive abortion laws.

- Outcome: The Court affirmed that the right to privacy includes the right to make medical decisions affecting one’s body and mental health.

Key Principle: Bodily and cognitive autonomy in medical decisions.

7. Sell v. United States (2003)

- Background: Dr. Charles Sell was ordered to take antipsychotic medication to render him competent for trial.

- Outcome: The Supreme Court ruled that forced medication to restore trial competency is permissible only in limited circumstances, reinforcing protections against involuntary alteration of one’s mental state.

Key Principle: Limits on forced cognitive alteration.

8. Ayahuasca and Religious Freedom Cases

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (2006):

- The Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not prohibit the União do Vegetal (UDV) church from using ayahuasca as a sacrament under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

- Key Principle: The right to explore consciousness for religious or spiritual purposes.

- Similar cases involve Native American groups using peyote, reinforcing cognitive liberty in the context of religious practices.

Emerging and Theoretical Cases

- Challenging Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI) and Neurotech:

- Potential future lawsuits could arise around the use of BCIs or neurotechnology that threaten cognitive privacy, such as unauthorized neural data collection or manipulation.

- Psychedelic Decriminalization Cases:

- As jurisdictions decriminalize substances like psilocybin (e.g., Oregon, Denver), challenges to federal prohibition laws could invoke cognitive liberty arguments.

- AI and Thought Privacy:

- The increasing capability of AI to infer mental states from data (e.g., facial expressions, biometric data) may prompt lawsuits around the right to mental privacy.

Core Legal Themes in Cognitive Liberty

- First Amendment: Freedom of thought, expression, and belief.

- Fourth Amendment: Protection against unreasonable searches of one’s mental processes (mental privacy).

- Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments: Due process and bodily autonomy.

- Religious Freedom: Protection of practices involving altered states of consciousness.

Cognitive liberty continues to evolve, with advancements in neuroscience, neurotechnology, and psychopharmacology raising new legal and ethical challenges.

Potential Future Legal Challenges in Cognitive Liberty

As technology advances and the boundaries between mental autonomy, privacy, and state intervention blur, cognitive liberty is likely to become more central to legal discourse. Here are some anticipated areas where cognitive liberty may be challenged:

1. Neuroprivacy and Brain Data Protection

- Context: With the rise of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), neural implants, and neuroimaging technology, companies and governments may seek to collect or analyze brain activity data.

- Potential Issues:

- Unauthorized collection or analysis of neural data by employers, insurers, or law enforcement.

- Surveillance applications that aim to predict or influence behavior based on brain data.

- Data breaches compromising sensitive neural information.

- Legal Frameworks to Watch:

- The Fourth Amendment (unreasonable searches and seizures).

- Biometric Data Privacy Laws (e.g., Illinois’ BIPA).

- Calls for new regulations specifically protecting “neural rights”.

- Hypothetical Case:

Doe v. NeuroCorp, where an employee sues their company for requiring neural scans to assess job performance, claiming a violation of mental privacy and cognitive autonomy.

2. Mandatory Neurointerventions

- Context: The potential use of brain stimulation or neuropharmacology for rehabilitation, education, or criminal reform.

- Potential Issues:

- Mandatory neurointerventions for prisoners to reduce recidivism.

- Cognitive enhancement requirements in educational or professional settings.

- Ethical concerns over altering behavior or personality through involuntary means.

- Relevant Precedents:

- Sell v. United States (2003): Limits on involuntary medication for trial competence.

- Riggins v. Nevada (1992): Protection against forced medication affecting trial fairness.

- Hypothetical Case:

Smith v. State of California, where a prisoner challenges a mandate to undergo brain stimulation therapy as a condition for parole, citing violations of bodily autonomy and cognitive liberty.

3. Psychedelics and Mental Autonomy

- Context: Growing acceptance of psychedelics for therapeutic and personal use (e.g., psilocybin, MDMA, ayahuasca).

- Potential Issues:

- Federal prohibition clashing with state-level decriminalization efforts.

- The right to explore altered states of consciousness for personal growth or mental health.

- Religious or spiritual use of psychedelics facing legal challenges.

- Relevant Cases:

- Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal (2006): Affirmed religious freedom for sacramental ayahuasca use.

- Employment Division v. Smith (1990): Limited religious use of peyote but sparked the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

- Hypothetical Case:

Johnson v. DEA, where an individual sues for the right to use psilocybin for mental health treatment, arguing that federal restrictions infringe on their cognitive liberty.

4. Artificial Intelligence and Mental Influence

- Context: AI tools capable of influencing decision-making, emotional states, or behavior through personalized algorithms.

- Potential Issues:

- Targeted manipulation of thoughts or beliefs through AI-driven content (e.g., social media algorithms).

- Coercive AI applications that exploit cognitive vulnerabilities.

- Use of AI to assess or predict mental states without consent.

- Legal Considerations:

- First Amendment protections against undue influence on thought.

- Privacy Laws regulating data collection and behavioral profiling.

- Hypothetical Case:

Garcia v. BigTechCorp, where a user claims an AI-driven platform manipulated their mental state, infringing on their right to cognitive self-determination.

5. Military and Cognitive Enhancement

- Context: The use of cognitive enhancements (e.g., stimulants, nootropics, neurostimulation) for soldiers to improve performance.

- Potential Issues:

- Whether soldiers can refuse cognitive enhancements.

- Long-term effects of mandatory cognitive interventions.

- Ethical concerns about the militarization of cognitive states.

- Relevant Principles:

- Bodily autonomy under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

- Informed consent in medical and military ethics.

- Hypothetical Case:

Doe v. Department of Defense, where a soldier challenges mandatory cognitive enhancements, claiming a violation of their cognitive liberty and bodily autonomy.

6. Cognitive Liberty in Education

- Context: Use of technology to monitor or influence student attention, focus, and behavior (e.g., eye-tracking software, brainwave monitors).

- Potential Issues:

- Whether schools can mandate cognitive monitoring tools.

- Potential discrimination based on cognitive data.

- Privacy concerns regarding student mental data.

- Hypothetical Case:

Brown v. School District, where a student’s family challenges the use of brainwave-monitoring headsets, claiming a violation of mental privacy and cognitive autonomy.

Legal and Policy Trends to Monitor

- Neural Rights Legislation: Countries like Chile are pioneering constitutional amendments to protect neural rights, setting a potential precedent for other nations.

- Biometric and Neural Data Protection: Expanding data protection laws to cover neural and cognitive data specifically.

- International Human Rights Law: Discussions at the United Nations about updating human rights frameworks to address cognitive liberty and mental privacy.

- Ethical Guidelines: Development of ethical guidelines for neurotechnology by organizations like the Neural Rights Foundation and IEEE.

Conclusion

Cognitive liberty is poised to become a defining issue of the 21st century, intersecting with advancements in neurotechnology, AI, psychedelics, and privacy law. As technology challenges the boundaries of mental autonomy, these lawsuits and legal principles will shape the future of our rights to control our thoughts, mental states, and cognitive processes.